It’s 2026, and if you’ve been filling prescriptions lately, you’ve probably noticed something off: some common meds just aren’t on the shelf. Not because they’re discontinued. Not because demand dropped. But because the companies that make them are caught in a financial vice grip - pricing pressure and shortages are squeezing them from both sides at once.

Why Are Essential Drugs Disappearing?

Think about insulin, antibiotics like amoxicillin, or even basic IV fluids. These aren’t luxury drugs. They’re basics. Yet, in 2025, the U.S. saw over 300 drug shortages, the highest number in a decade. The World Health Organization flagged 12 critical medicines with global supply risks. And behind every empty shelf is a manufacturer losing money just to make the product.

It’s not about greed. It’s about math that no longer adds up. The cost to produce a single vial of a generic antibiotic has jumped 18% since 2023. Raw materials like active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) - many of which come from India and China - have become more expensive due to export restrictions, climate disruptions, and new tariffs. In 2025 alone, tariffs on key chemical imports rose to an average of 11.5%, up from 2.4% just two years earlier. That’s not a small bump. That’s a tax on every pill, every injection, every dose.

But here’s the catch: hospitals and insurers won’t pay more. They’ve locked in fixed prices for years. Manufacturers can’t raise prices without losing contracts, and they can’t cut costs without risking quality or safety. So they’re stuck. Some cut production runs. Others shift focus to more profitable drugs - like those for chronic conditions that pay better. And that’s how the basics vanish.

The Domino Effect: From Factory Floor to Pharmacy

It’s not just one problem. It’s a chain reaction. When a manufacturer can’t make enough of a drug because raw materials are too expensive or delayed, they reduce output. That means fewer units available. Fewer units means pharmacies can’t stock enough. Pharmacies then start rationing. Doctors have to switch patients to alternatives - sometimes less effective, sometimes more expensive, sometimes just harder to get.

Take the case of injectable corticosteroids used in emergency rooms. In late 2024, a single supplier in China halted exports due to environmental compliance issues. The U.S. had no backup. Within months, hospitals were using half-doses or delaying treatments. The FDA reported 14% more patient delays in steroid-dependent conditions in Q1 2025. That’s not a glitch. That’s systemic.

And it’s not just generics. Even branded drugs are feeling the heat. A major U.S. oncology drug maker cut its production of a $1,200-per-dose chemotherapy agent by 30% in 2025 because the cost of a single chemical component rose 42%. They couldn’t raise the price - Medicare reimbursement caps wouldn’t allow it. So they made less. Patients waited. Some missed treatments.

Who’s Paying the Price?

Manufacturers aren’t the only ones hurting. Patients are. Nurses are. Clinics are. When a drug is in short supply, hospitals scramble. They pay premium prices on the gray market. They use substitute drugs that may cause side effects. They delay surgeries. They transfer patients to other facilities. All of it costs more - and it’s all passed on to the system.

One hospital administrator in Ohio told me their pharmacy budget jumped $1.2 million in 2025 just to cover shortages. That’s not inflation. That’s emergency spending. And it’s happening in every state. The American Hospital Association estimates drug shortages added $1.8 billion in extra costs to U.S. hospitals in 2025 alone.

Meanwhile, patients are paying more out of pocket. Insurers are increasing copays for alternative drugs. Some patients skip doses. Others go without. A 2025 survey by the National Consumers League found 21% of chronic illness patients reported skipping or cutting pills because of cost or availability. That’s one in five.

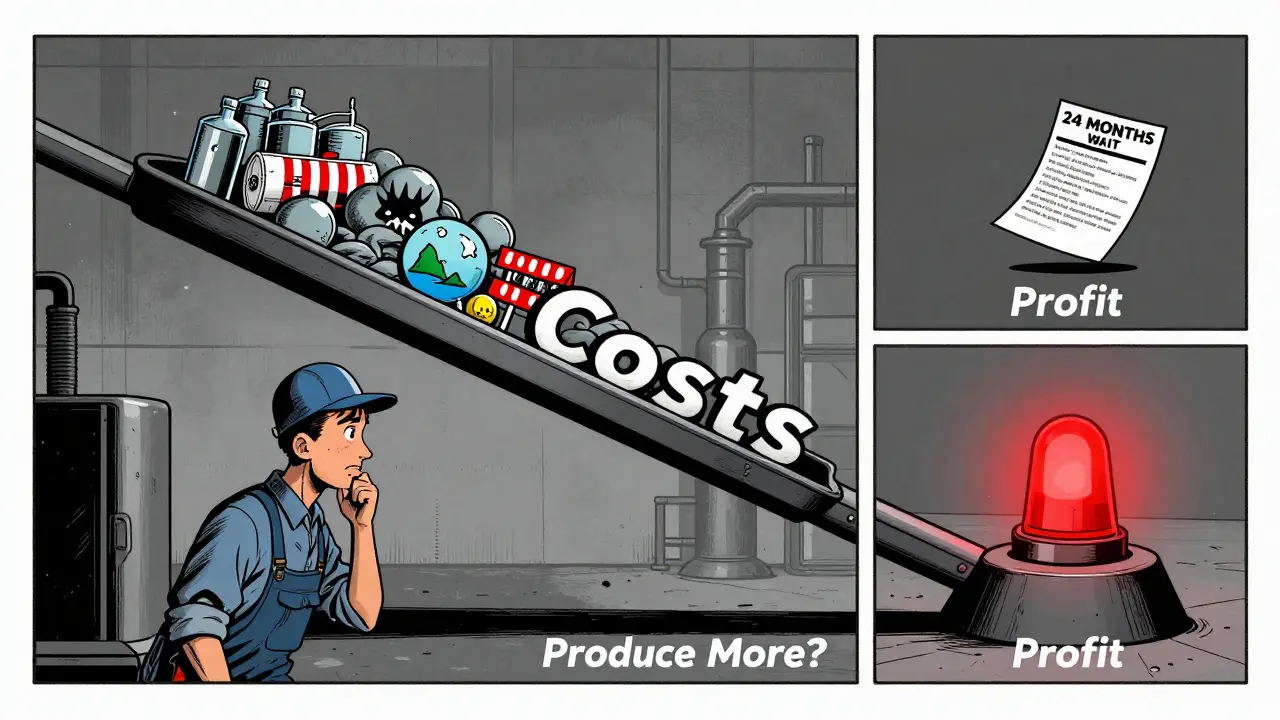

Why Can’t Manufacturers Just Make More?

You’d think the answer is simple: build more factories. Hire more workers. Order more materials. But it’s not that easy.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing is tightly regulated. Getting FDA approval for a new production line takes 18-24 months. Building a facility costs $100 million or more. And if you invest in making one drug, you’re betting everything on its price staying stable - which it won’t. If the price drops next year because of new government pricing rules, you’re stuck with a $100 million asset that barely breaks even.

That’s why most manufacturers play it safe. They stick to the cheapest, lowest-margin drugs - the ones that are easy to make and don’t need fancy tech. But those are exactly the ones getting hit hardest by rising costs. It’s a trap. The more they focus on low-cost generics, the more they lose money. The more they lose money, the less they invest. The less they invest, the more shortages grow.

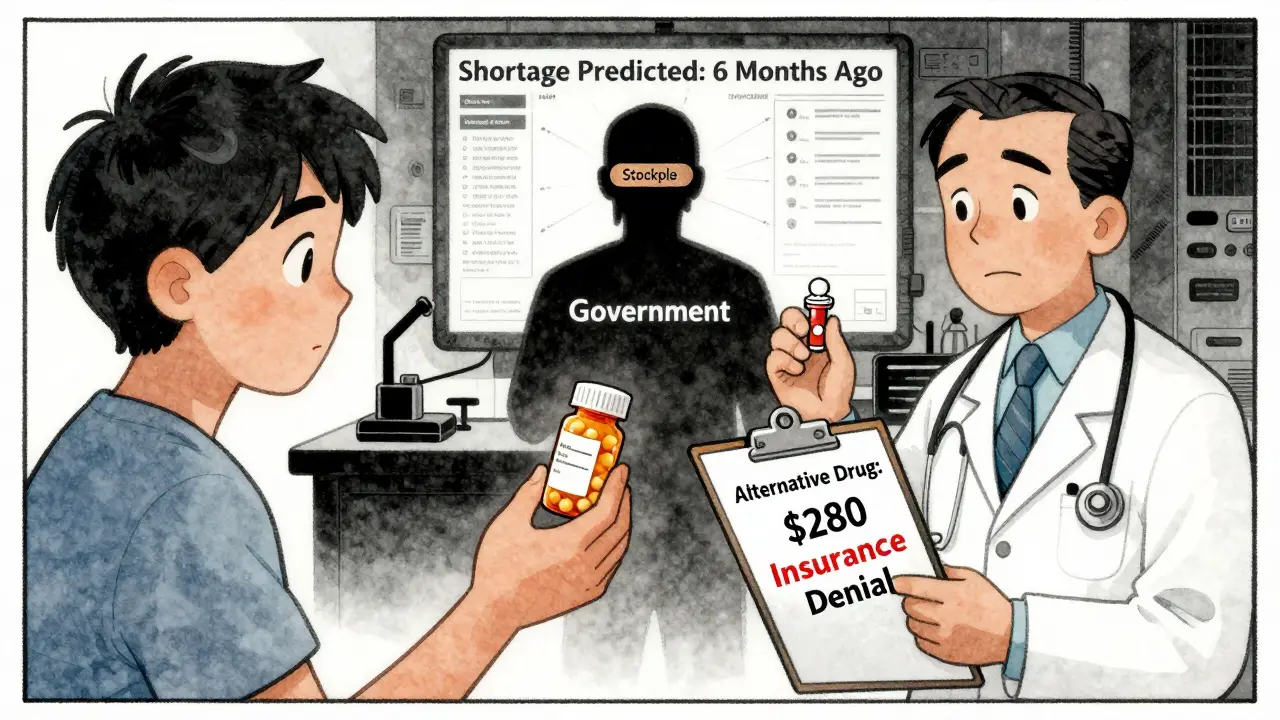

The Digital Fix: Can Technology Save Us?

Some companies are trying to break the cycle. A handful of mid-sized manufacturers are using AI-driven forecasting tools to predict shortages before they happen. One company in New Jersey started tracking global shipping delays, weather patterns in India, and even political unrest in key chemical-exporting regions. Their system flagged a potential API shortage six months before it hit - and they reordered early, avoiding a 90-day gap in production.

Others are using dynamic pricing models - not to jack up prices, but to make smarter decisions. Instead of charging the same for every batch, they adjust slightly based on real-time input costs. That lets them stay profitable without triggering backlash from insurers. One firm reported reducing margin erosion from 8.3% to just 2.1% in 2025 using this method.

And then there’s nearshoring. More companies are moving production from Asia to Mexico or Eastern Europe. It’s not cheaper, but it’s more predictable. Shipping times drop from 45 days to 12. Tariffs are easier to manage. And if something breaks down, engineers can fly in within 24 hours instead of waiting a week.

But here’s the problem: only 14% of generic drug makers have the capital to do this. The rest? They’re still waiting for a miracle.

What’s Next? The Road Ahead

Experts agree: this isn’t a temporary glitch. It’s a structural shift. The days of ultra-cheap, globalized drug manufacturing are over. The cost of doing business has changed - permanently. Tariffs, climate risks, geopolitical tensions, and labor shortages aren’t going away. And the pressure on margins won’t ease unless something changes.

The FDA has started fast-tracking approvals for backup suppliers. The government is funding domestic API production through the CHIPS and Science Act extensions. Some states are creating drug stockpiles. But these are Band-Aids. What’s needed is a new economic model - one that pays manufacturers fairly for making essential, low-margin drugs.

Imagine if the government guaranteed a minimum profit margin - say, 8% - on all drugs deemed critical for public health. Not a subsidy. Not a price freeze. Just a floor. That would give manufacturers the confidence to invest. To build. To hire. To make sure the next insulin shortage never happens.

Right now, we’re treating drug shortages like a logistics problem. But it’s a financial one. Until we fix the money side, the shelves will keep emptying. And patients will keep paying the price.

Why are generic drugs in short supply when they’re supposed to be cheap to make?

Generic drugs are cheap to make - but only if the raw materials and labor stay cheap. Since 2023, the cost of active ingredients has risen 15-25% due to tariffs, supply chain disruptions, and export controls. At the same time, insurers and Medicare won’t pay more for generics. So manufacturers either lose money making them or stop making them altogether. The cheapest drugs are now the least profitable - and that’s why they’re disappearing.

Can the U.S. just make more drugs domestically?

Yes - but it’s slow and expensive. Building a single FDA-approved drug manufacturing facility costs over $100 million and takes two years. Even then, you need a steady supply of raw materials, which often still come from overseas. Without guaranteed profits, no company will risk that kind of investment. The government is offering grants, but they’re not enough to cover the full cost or the risk of future price caps.

Are drug shortages getting worse in 2026?

Yes. Data from the FDA and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists shows shortages increased by 12% in the first six months of 2026 compared to the same period in 2025. The biggest spikes are in antibiotics, IV fluids, and hormone therapies. Rising costs, combined with new export restrictions from India and China, are making the problem worse. Without policy changes, shortages will keep climbing.

How do tariffs contribute to drug shortages?

Tariffs on chemical imports - especially active pharmaceutical ingredients - have jumped from 2.4% in early 2025 to 11.5% by mid-year. That adds $0.50-$2.00 to the cost of a single vial of a generic drug. Since insurers won’t pay more, manufacturers either absorb the loss (and cut production) or stop making the drug entirely. In 2025, 63% of manufacturers said tariffs directly caused them to reduce output on at least one essential drug.

What can patients do if their medication is unavailable?

Talk to your doctor immediately. Don’t skip doses or substitute without guidance. Pharmacists can often suggest FDA-approved alternatives or help you access emergency supplies through hospital networks. Some manufacturers also offer patient assistance programs for those affected by shortages. Check the FDA’s Drug Shortages page for real-time updates and alternatives. But the real solution? Advocating for policies that ensure manufacturers can profitably produce essential drugs.

Jasmine Bryant on 23 January 2026, AT 01:45 AM

ive been filling scripts for 12 years and this is the first time i’ve had to tell patients to wait weeks for amoxicillin. it’s not just inconvenient-it’s dangerous. my grandma’s on insulin and we’ve had to switch brands twice this year. no one’s talking about how this affects elderly folks who can’t just ‘try something else’.