When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might wonder: is this really the same as the brand-name drug your doctor prescribed? The answer isn’t as simple as ‘yes’ or ‘no’-but it’s far more controlled than most people think. The key concept here is pharmaceutical equivalence. It’s the first and most basic rule that generic drugs must follow before they even get close to being sold. And understanding it can help you feel more confident about switching to a lower-cost option.

What pharmaceutical equivalence actually means

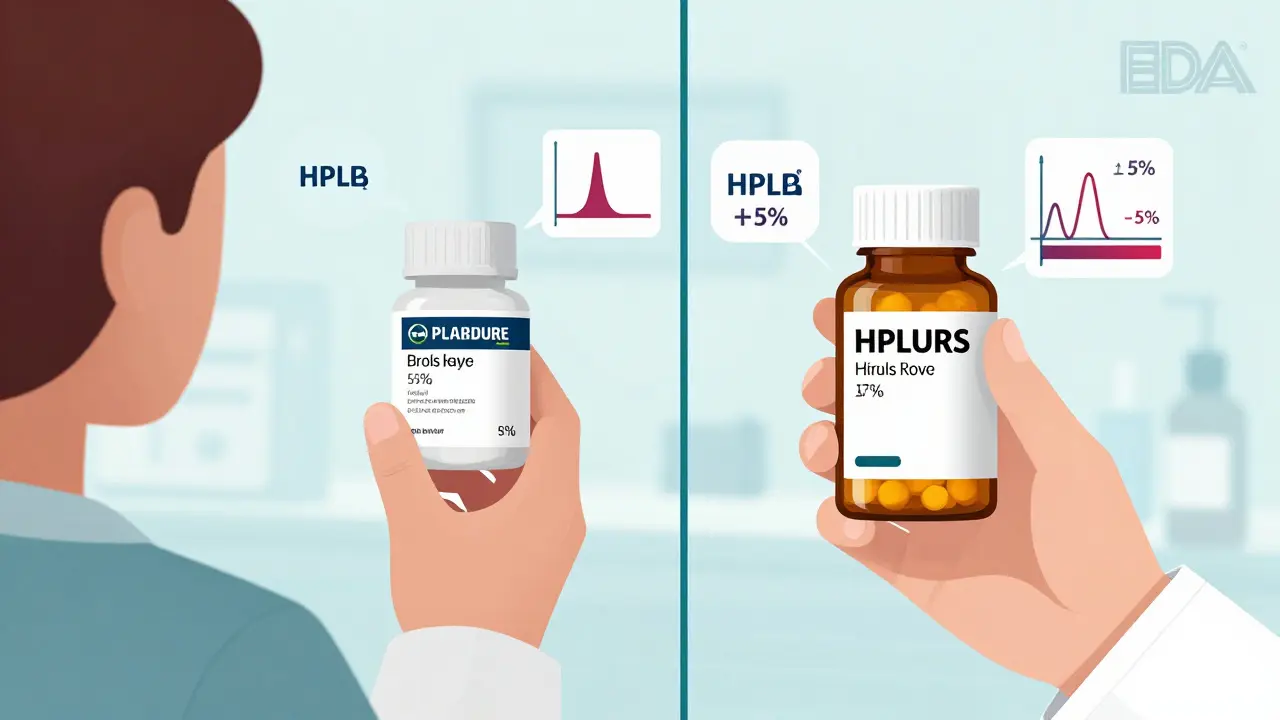

Pharmaceutical equivalence means two things: the generic drug and the brand-name drug have exactly the same active ingredient, in the same amount, in the same form, and delivered the same way. That’s it. No more, no less. If your brand-name drug is a 50 mg tablet taken by mouth, the generic must also be a 50 mg tablet taken by mouth-and it must contain precisely the same chemical compound as the active ingredient. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires this to be verified using lab tests like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which measures the exact amount of the drug in the tablet. The acceptable margin? Within ±5% of the labeled amount. That’s tighter than most people realize.It doesn’t matter what color the pill is. It doesn’t matter if the generic is round and the brand is oval. It doesn’t matter if the generic uses cornstarch instead of lactose as a filler. Those are inactive ingredients-excipients-and they’re allowed to differ. As long as those differences don’t change how the drug works in your body, they’re fine. The FDA doesn’t require generics to match the brand’s packaging, taste, or even the imprint on the tablet. Only the active ingredient has to be identical.

Why this matters more than you think

You might think, “If the active ingredient is the same, then it’s the same drug.” And for most people, that’s true. But pharmaceutical equivalence is just the starting line. It doesn’t guarantee the drug will work the same way in your body. That’s where bioequivalence comes in-and it’s the next step in the process.Think of pharmaceutical equivalence like having two identical engines. One is in a Toyota, the other in a Honda. Same parts, same design. But if one engine is tuned to burn fuel slower, or if the air intake is different, the car might not perform the same on the road. That’s bioequivalence: does the drug get into your bloodstream at the same rate and in the same amount? The FDA requires generics to show that their drug’s absorption matches the brand within an 80% to 125% range for two key measurements: total exposure (AUC) and peak concentration (Cmax). That’s a wide window-but it’s based on real-world biological variation. Your body absorbs drugs differently from day to day, even with the same pill. The 80-125% range accounts for that.

So pharmaceutical equivalence says: “Same active ingredient, same amount.” Bioequivalence says: “Same amount gets into your blood, same speed.” Only after both are proven can a drug be rated as therapeutically equivalent-meaning it can be safely substituted without any expected difference in how well it works or how safe it is.

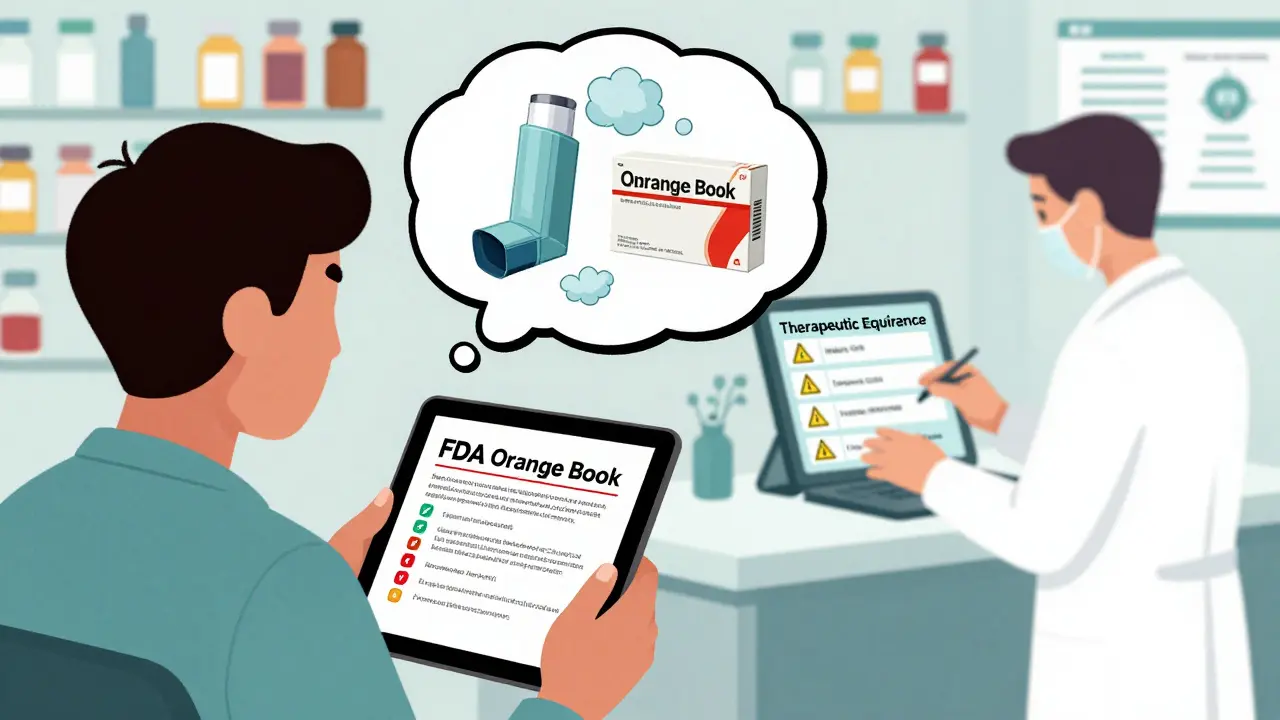

The Orange Book: Your secret guide to generic safety

Every month, the FDA updates a public database called the Orange Book. It lists every approved drug-brand and generic-and rates them by therapeutic equivalence. If a generic is rated “AB,” it means it’s pharmaceutically and bioequivalent to the brand. You can trust it. If it’s rated “BX,” it’s not considered interchangeable. That could be because of formulation issues, delivery problems, or lack of bioequivalence data.As of June 2024, there were over 15,000 approved generic drugs in the U.S. More than 12,800 of them had an “AB” rating. That’s the vast majority. But not all. Some complex drugs-like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams-can have multiple generics with the same active ingredient but different delivery systems. For example, two generic asthma inhalers might have the same active drug, but one uses a different propellant. That changes how the medicine reaches your lungs. Even if they’re pharmaceutically equivalent, they’re not therapeutically interchangeable. Pharmacists won’t substitute them without checking the Orange Book rating.

What happens when things go wrong?

Most of the time, generics work just fine. But sometimes, patients report side effects after switching. That’s usually not because the active ingredient changed. It’s because of the excipients.A 2022 survey found that 87% of pharmacists had seen at least one patient react to an inactive ingredient in a generic drug. Common culprits? Dyes, preservatives, or fillers like gluten, lactose, or artificial coloring. If you’re allergic to sulfites, or you have celiac disease, a change in excipients could cause bloating, rash, or even anaphylaxis in rare cases. That’s why some patients need to stick with the brand-because their body reacts to something in the generic’s coating or binder.

And here’s a myth that still circulates: many patients think generics contain only 80% of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. The 80% figure comes from bioequivalence limits-not pharmaceutical equivalence. A generic tablet still contains 100% of the labeled active ingredient. The 80-125% range refers to how much of that ingredient actually gets into your bloodstream, not what’s in the pill.

Who decides if you get a generic?

In most states, pharmacists can substitute a generic for a brand-name drug unless the doctor writes “Dispense As Written” or “Do Not Substitute.” But they can’t just pick any generic. They have to choose one with an “AB” rating. Most pharmacies use automated systems that pull the Orange Book rating when filling a prescription. If a generic has a “BX” rating, the system won’t allow substitution.Hospitals are even stricter. A 2023 survey found that 68% of U.S. hospitals require a pharmacist to personally verify the therapeutic equivalence rating before switching a patient’s medication. That’s because inpatient care is more sensitive. A small change in blood levels of a seizure drug or blood thinner could be dangerous.

Why pharmaceutical equivalence saves billions

Since the Hatch-Waxman Act passed in 1984, generic drugs have saved the U.S. healthcare system over $2.2 trillion. In 2023 alone, the average cost of a generic prescription was $1,008 less than the brand-name version. That’s not just money saved-it’s access. A patient who can’t afford a $500 monthly drug might be able to take a $40 generic. Pharmaceutical equivalence makes that possible without compromising safety.And the system keeps improving. In 2022, the FDA launched GDUFA III, a program that cut the average approval time for generics from 24 months to 18. They’re also investing $15 million into new testing methods like Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction to better analyze complex drugs-like those with delayed-release coatings or nanoparticles. These tools help ensure that even the trickiest generics meet pharmaceutical equivalence standards.

What you should do

If you’re prescribed a generic, you don’t need to worry. For most drugs, the system works exactly as designed. But if you’ve had a bad reaction after switching, tell your doctor and pharmacist. Ask: “Is this generic rated AB in the Orange Book?” You can check it yourself at the FDA’s website-no login needed.Don’t assume all generics are the same. If you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or lithium-ask your pharmacist if there’s only one approved generic. Sometimes, even two “AB” rated versions can behave differently in your body. In those cases, sticking with the same manufacturer matters.

And if you’re concerned about excipients, ask for the full ingredient list. Pharmacies can provide it. You don’t have to guess whether your generic contains gluten or dye. Knowledge is power-and in this case, it’s safety.

What’s next for generic drugs

The FDA is working on new rules that will require more detailed reporting of excipients, especially for drugs where the filler affects how the medicine releases. That’s because some newer drugs rely on specific coatings or gels to control absorption. Change the coating, and you change how the drug works-even if the active ingredient is identical.By 2027, we’ll likely see more advanced testing used in routine approval. That means even more confidence in generics-even the complex ones. But the core rule won’t change: same active ingredient, same amount, same form. That’s pharmaceutical equivalence. And it’s the foundation of everything else.

Art Van Gelder on 21 December 2025, AT 11:56 AM

So let me get this straight - the pill can be neon green, shaped like a star, taste like burnt popcorn, and still be legally identical to the brand? I mean, I get the science, but man, it’s wild how much of medicine is just… theater. The active ingredient is the only thing that matters? That’s like saying two BMWs are the same because they both have a 3.0L engine, even if one’s got a cardboard dashboard and the other’s got leather and a 12-speaker sound system. The engine might be identical, but the whole experience? Totally different. And yet we’re supposed to just swallow it - literally and figuratively.

It’s not about the drug. It’s about the trust. And trust? That’s not regulated by the FDA.

Also, who decided that 80-125% absorption is ‘close enough’? That’s like saying ‘your weight loss is fine as long as it’s between 5 and 15 pounds.’ Sure, mathematically it’s within range… but if I’m trying to lose 10 and I lose 14, I’m not celebrating. I’m panicking.

Anyway. Still cheaper. Still works for most. Just… weird to think about.