When a drug sends your body into crisis-hives spreading across your skin, your throat closing, or your skin peeling off-you don’t just avoid that one pill. You start wondering: Do I need to avoid the whole family? It’s a terrifying question, and the answer isn’t always simple. Too often, patients are told to avoid entire classes of drugs based on a single bad reaction, even when it’s not necessary. That can mean years of missed treatments, unnecessary risks, and longer hospital stays. But not every bad reaction means you’re allergic to everything in that group. Knowing when to draw the line-and when not to-can save your life.

Not All Reactions Are Allergies

People say they’re "allergic" to penicillin because they got a rash after taking it. But 90% of the time, that’s not an allergy at all. It’s a side effect. True allergic reactions involve your immune system. They happen fast-within minutes to hours-and include symptoms like swelling of the tongue or lips, trouble breathing, a drop in blood pressure, or anaphylaxis. These are emergencies. But a mild rash that shows up days later? That’s often just your body reacting to the drug’s chemistry, not attacking it like a virus.

The difference matters. If you had a rash from amoxicillin as a kid and were labeled "penicillin allergic," you might be denied life-saving antibiotics for pneumonia or a severe infection. But studies show that 95% of people who think they’re allergic to penicillin can actually take it safely after proper testing. The label sticks because doctors don’t always dig deeper. And when they don’t, you end up on stronger, more expensive, or riskier drugs just because of a mislabel.

When Avoiding the Whole Family Is Necessary

There are reactions where avoiding the entire class isn’t just smart-it’s critical. These are the ones that attack your body on a systemic level. Think Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), or DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms). These aren’t rashes. They’re life-threatening. TEN alone kills 30 to 50% of people who get it. And once you’ve had it, the risk of getting it again-even with a different drug in the same family-is extremely high.

These reactions are most often tied to just six drug classes: sulfonamide antibiotics (like Bactrim), anticonvulsants (like carbamazepine), allopurinol (for gout), NSAIDs, nevirapine (for HIV), and corticosteroids. If you’ve had SJS or TEN from one of these, you need to avoid all drugs in that class. There’s no safe dose. No "maybe." The European Medicines Agency found that 95% of TEN cases come from just these six classes. That’s not coincidence-it’s a pattern you can’t ignore.

Even if you didn’t have a full-blown SJS, but you had a severe skin reaction with fever, swollen lymph nodes, and organ involvement (DRESS), you’re still at high risk. These reactions are delayed-sometimes weeks after taking the drug-but they’re just as dangerous. Once you’ve had one, you’re not just avoiding one drug. You’re avoiding the whole family.

Cross-Reactivity: The Hidden Trap

Not all drugs in a family behave the same. But some do. The biggest example? Beta-lactam antibiotics. Penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems all share a similar chemical structure. That means if you’re truly allergic to penicillin, you might also react to cefalexin or meropenem. But here’s the twist: the risk isn’t as high as people think. Cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins is only 0.5% to 6.5%, depending on the specific drugs. That’s low enough that many doctors now recommend testing before ruling out all beta-lactams.

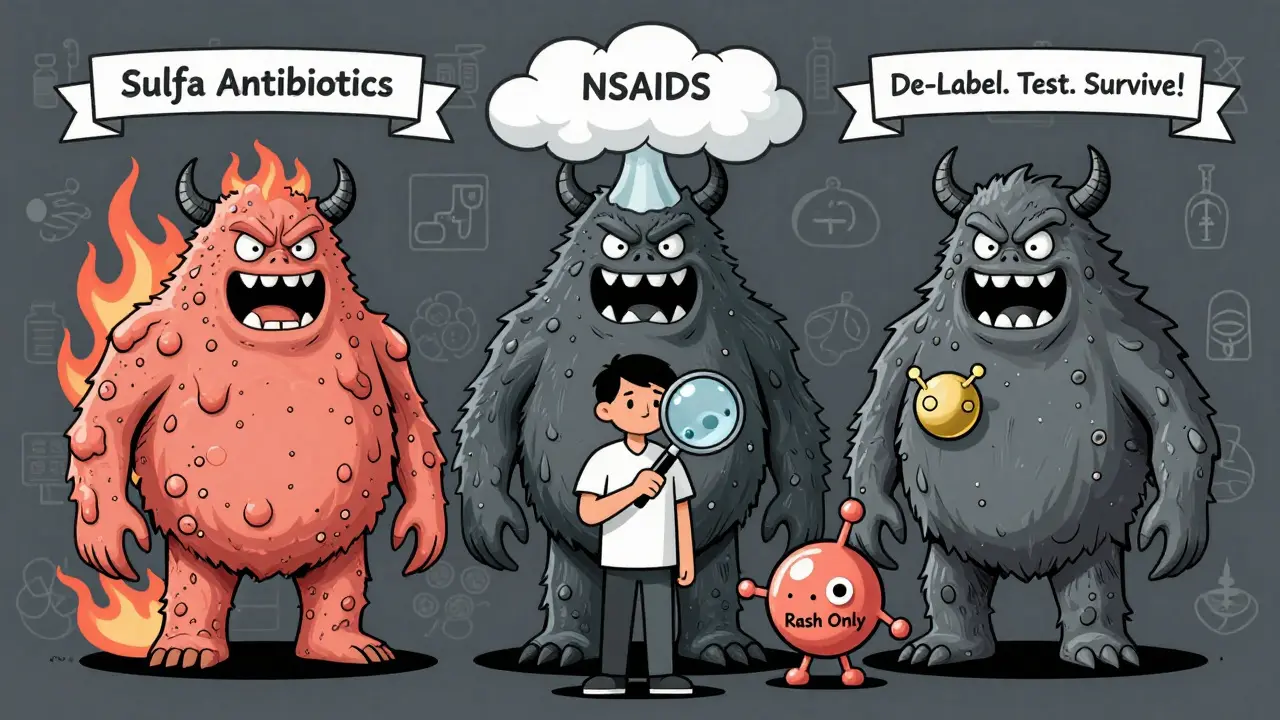

Sulfa drugs are another trap. Bactrim (sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim) is a sulfa antibiotic. But so is furosemide (Lasix), a water pill, and celecoxib (Celebrex), a painkiller. If you had a severe reaction to Bactrim, you might be told to avoid all sulfa drugs. But here’s the catch: the allergic reaction is usually to the sulfonamide part. Drugs like furosemide and celecoxib have a different chemical structure. Studies show cross-reactivity is only about 10%. That means you might be able to take a water pill or arthritis medicine safely-even if you reacted to an antibiotic.

NSAIDs are trickier. If you have aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease-where you get asthma attacks or nasal polyps after taking aspirin or ibuprofen-you’re likely to react to most NSAIDs. That’s because it’s not an allergy. It’s a pharmacological reaction. Your body can’t process these drugs properly, and they trigger inflammation in your airways. About 70% of people with this condition react to multiple NSAIDs. But COX-2 inhibitors like celecoxib may be safer. They don’t trigger the same pathway. So avoidance isn’t always total-it’s targeted.

De-Labeling: The Forgotten Solution

Too many people live with a drug allergy label they don’t need. One patient on HealthUnlocked spent 20 years avoiding penicillin after a childhood rash. She finally got tested. Skin and blood tests showed no allergy. She took amoxicillin for a sinus infection-no problem. That’s de-labeling. And it’s becoming more common. In 2023, 87% of academic medical centers in the U.S. had formal penicillin allergy assessment programs. They don’t just ask, "Did you have a reaction?" They ask: What happened? When? How bad? Did you need epinephrine?

These programs use tools like the DELPHI instrument, which predicts cross-reactivity risk with 89% accuracy. They also use drug challenges-giving a small, controlled dose under medical supervision. Success rates for beta-lactam challenges are 70 to 85% in low-risk patients. That means for most people labeled allergic, the answer isn’t "never again." It’s "try again, safely."

The FDA and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology both say: don’t assume. Test. Confirm. De-label. Avoiding a whole drug family without proof isn’t caution-it’s overkill. And overkill leads to worse outcomes. Patients with false allergy labels are more likely to get broader-spectrum antibiotics, which increase the risk of C. diff infections and antibiotic resistance.

What to Do After a Severe Reaction

If you’ve had a severe reaction, here’s what to do next:

- Write it down. What drug? What symptoms? When did they start? Did you go to the ER? Did you need epinephrine or steroids? Write the exact name of the drug-not "antibiotic" or "painkiller."

- Update your records. Make sure your EHR has the full description. "Rash" isn’t enough. "Anaphylaxis after amoxicillin, required epinephrine, resolved in 30 minutes" is. Use standardized terms like SNOMED CT codes if possible.

- Ask for a referral. If it was a skin reaction, breathing issue, or anaphylaxis, ask your doctor for an allergist. Don’t wait. The sooner you get tested, the sooner you can stop avoiding drugs you might still tolerate.

- Consider medical alert jewelry. If you’ve had anaphylaxis or a SCAR, wear a bracelet or necklace that says "Penicillin Allergy - Anaphylaxis" or "Sulfa Allergy - SJS." It can save your life in an emergency.

- Don’t assume all drugs in the class are off-limits. Just because you reacted to one doesn’t mean you can’t take another. Ask your doctor: "Is there a safer alternative in this class? Or a completely different class?"

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Every year, over 1.3 million Americans end up in the ER because of bad drug reactions. About 350,000 are hospitalized. And a huge chunk of those are preventable. Many happen because doctors don’t know what the patient truly reacted to. They see "penicillin allergy" in the chart and assume the worst. They give vancomycin instead of amoxicillin. Vancomycin is stronger, more expensive, and can damage kidneys. It’s not better-it’s a backup plan turned default.

There’s progress. The FDA’s Safer Technologies Program is funding new diagnostic tools. The NIH’s All of Us program found that a single gene-HLA-B*57:01-can predict who will react to abacavir (an HIV drug) with near-perfect accuracy. That means instead of avoiding the drug for everyone, we can test before giving it. That’s precision medicine. And it’s coming to more drug classes.

But until then, you have to be your own advocate. If you’ve had a severe reaction, don’t just accept the label. Ask questions. Push for testing. Demand clarity. The goal isn’t to avoid every drug. The goal is to avoid the right ones-and keep the rest within reach.

When You Can Still Use a Drug Family

Here’s the truth: many people avoid entire drug families out of fear, not science. If you had a mild rash from amoxicillin that didn’t involve swelling, breathing trouble, or fever, you probably don’t need to avoid all penicillins. If you had stomach upset from ibuprofen but no asthma flare-up, you might tolerate naproxen or celecoxib. If you had a rash from sulfamethoxazole but never had organ failure or blistering skin, you might still safely take furosemide or celecoxib.

The key is distinguishing between immune-driven reactions (true allergies) and pharmacological ones (side effects). The former demands caution. The latter can often be managed with a switch within the class or a different drug altogether.

Don’t let a past reaction become a life sentence. You deserve better treatment-not just safer, but more effective, more affordable, and more appropriate. And you can get it-if you know when to push back.

If I had a rash from penicillin, do I need to avoid all antibiotics in that family?

Not necessarily. A mild rash that appears days after taking the drug is often not an allergy-it’s a side effect. True penicillin allergies involve immune responses like hives, swelling, or anaphylaxis within minutes to hours. Studies show 95% of people labeled "penicillin allergic" can safely take penicillin after testing. If your reaction was mild and delayed, ask your doctor about an allergist referral and skin testing.

Can I take a sulfa-based painkiller if I had a reaction to a sulfa antibiotic?

Possibly. True sulfa allergies are usually linked to sulfonamide antibiotics like Bactrim. Painkillers like celecoxib (Celebrex) and diuretics like furosemide (Lasix) contain a different chemical structure. Cross-reactivity is only about 10%. If you had a mild rash or stomach upset, you may be able to take them safely. But if you had Stevens-Johnson syndrome or anaphylaxis, avoid all sulfa-containing drugs. Always consult an allergist before trying any.

Is it safe to try a drug I was allergic to again?

Only under medical supervision. Drug challenge tests-where you’re given a small, controlled dose in a clinic-are safe and effective for many people. Success rates are 70-85% for beta-lactam antibiotics in low-risk patients. Never try this at home. But if you’ve been avoiding a drug for years due to a mild reaction, a challenge might restore your options and prevent unnecessary use of stronger, riskier alternatives.

What’s the difference between an allergic reaction and a side effect?

An allergic reaction involves your immune system and usually happens quickly-within minutes to hours. Symptoms include hives, swelling, wheezing, or anaphylaxis. Side effects are predictable based on how the drug works. For example, nausea from antibiotics or stomach bleeding from NSAIDs. Side effects don’t mean you’re allergic. They mean the drug has known risks. You might still be able to use it with monitoring or a different dose.

Can I outgrow a drug allergy?

Yes, especially with penicillin. About 80% of people who had a true penicillin allergy in childhood lose it after 10 years. That’s why retesting is so important. If you were told you were allergic 15 or 20 years ago, you might be able to take it again now. Don’t assume the label still applies. Ask for testing.

Why do doctors sometimes avoid entire drug families after one bad reaction?

It’s often out of caution-and fear of liability. Many doctors don’t have time or training to assess reaction details. If a patient had a severe reaction, avoiding the whole class seems safer than risking another. But this leads to overuse of broader-spectrum antibiotics and higher rates of resistant infections. Better documentation, allergist referrals, and de-labeling programs are changing this, but it’s still common.