When a new drug hits the market, the clock starts ticking on its monopoly. The primary patent gives the maker 20 years to profit before generics can step in. But in reality, many blockbuster drugs stay off-limits to cheap copies for two decades or more-not because of one patent, but because of a web of secondary patents. These aren’t about the active ingredient itself. They’re about the packaging, the timing, the form, or even the way it’s used. And they’re the main reason why a pill that should cost $5 can still cost $500.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

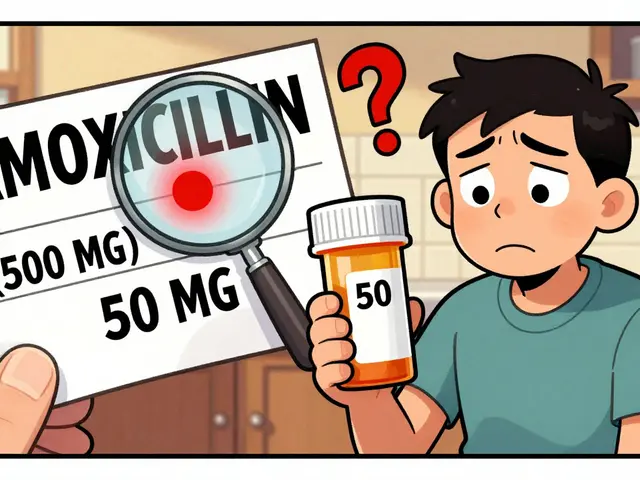

A secondary patent doesn’t protect the molecule. It protects something around it. Think of it like upgrading a car. The engine is the primary patent-the core technology. Secondary patents are the new tires, the upgraded sound system, the special paint job. They’re real innovations, sometimes. But often, they’re small tweaks that don’t improve how the drug works for patients-just how the company sells it. The most common types include:- Formulation patents: Protecting a new pill shape, a slow-release version, or a liquid instead of a tablet. AstraZeneca’s switch from Prilosec to Nexium (the same active ingredient, just one mirror-image molecule) extended exclusivity by nearly a decade.

- Method-of-use patents: Claiming the drug treats a new disease. Thalidomide was originally a sedative. Decades later, it got a patent for leprosy. Then again for multiple myeloma. Each time, the clock reset.

- Polymorph patents: Protecting a different crystal structure of the same chemical. GlaxoSmithKline used this to delay generics for Paxil even after the original patent expired.

- Combination patents: Pairing the drug with another compound. Even if the second drug is generic, the combo gets its own protection.

Some drugs have over 100 secondary patents. Humira, AbbVie’s top-selling arthritis drug, had 264. The primary patent expired in 2016. But because of this thicket, no generic could enter until 2023. During that time, Humira brought in over $20 billion annually.

Why Do Companies Build Patent Thickets?

It’s simple math. A single blockbuster drug can make $1 billion a year. Losing that to generics means a 90% revenue drop overnight. The cost of developing a new drug? Around $2.6 billion. So companies pour money into extending their window. Secondary patents aren’t random. They’re planned years in advance. Lifecycle management teams start filing them 5 to 7 years before the main patent runs out. They time new versions to launch just before generics hit-so doctors and patients get used to the new pill, the new dose, the new delivery system. Then, when the old patent expires, the company says, “Why switch back to the old version?” This is called “product hopping.” And it works. A 2019 Health Affairs study found that drugs with secondary patents face generic entry delays that are 2.3 years longer than those without. In the U.S., 68% of method-of-use patents successfully blocked generics for their specific indication.

Who Pays the Price?

Patients don’t pay the patent bills. But they pay the price tags. Pharmacy benefit managers like Express Scripts say secondary patents raise their costs by 8.3% every year. Insurers pass that on to you in higher premiums and copays. Medicare spends billions each year on drugs still under secondary patent protection. In 2023, the average cost of a drug with a secondary patent was 4.5 times higher than its generic equivalent. Patient groups see both sides. Some, like the American Cancer Society, point to real wins-new formulations of chemo drugs that cut severe side effects by 37%. But others, like Knowledge Ecology International, highlight the cost of abuse. Humira’s 264 patents? They kept the price sky-high while the drug’s core formula stayed unchanged for over 20 years. Generic manufacturers don’t stand idle. They file Paragraph IV certifications-legal challenges to secondary patents. In 2022, 92% of listed secondary patents were challenged. But only 38% of those challenges succeeded. Why? Because the legal system favors the deep pockets of big pharma. Legal battles cost $15-20 million per drug. Most generics can’t afford to fight more than one or two.Global Differences: Where Secondary Patents Don’t Work

The U.S. is the biggest playground for secondary patents. But not everywhere. India’s patent law, since 2005, says you can’t patent a new version of an old drug unless it shows “enhanced efficacy.” That stopped Novartis from patenting a new crystalline form of Gleevec. India got generics within months. Brazil requires approval from its health ministry before a patent can be enforced. That’s a high bar. Countries like Thailand and South Africa have used compulsory licensing to override secondary patents when drugs are too expensive for public health needs. The European Union is shifting too. In 2023, the European Commission called out “patent thickets” as a barrier to affordable medicines. They’re now pushing for stricter reviews of secondary patents-especially those with no clear clinical benefit.

The Debate: Innovation or Exploitation?

PhRMA, the drug industry’s main lobbying group, says secondary patents drive innovation. CEO Stephen Ubl claims they’ve led to safer dosing, better delivery, and new uses for rare diseases. And there’s truth there. A new formulation that reduces nausea or lets patients take a pill once a day instead of four? That’s valuable. But Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim looked at hundreds of secondary patents and found only 12% offered meaningful clinical improvements. The rest? Minor changes designed to delay competition. The numbers back him up. A 2012 PLOS ONE study showed that for every extra billion dollars a drug made in sales, the company’s chance of filing a secondary patent went up by 17%. That’s not innovation driven by patient need. That’s profit-driven. The U.S. government is starting to push back. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act lets Medicare challenge certain secondary patents. The FDA is also reviewing which patents get listed in the Orange Book-the official list generics use to know what to challenge. Only formulation and method-of-use patents can be listed. Manufacturing processes? Even if they’re patented, they’re hidden. That’s a loophole.What’s Next?

The era of unchecked secondary patenting might be ending. Courts are getting stricter. In 2023, the Federal Circuit narrowed the scope of antibody patents-a big blow to one of the most abused types of secondary claims. Analysts predict that by 2027, companies will need to prove real clinical benefit to keep their secondary patents. Investors are starting to ask: Is this innovation, or just legal gymnastics? Meanwhile, generic makers are getting smarter. They’re teaming up. They’re sharing legal costs. They’re filing challenges in batches. And they’re targeting the weakest patents first-the ones with vague claims or weak evidence. The future of drug pricing doesn’t just depend on who makes the medicine. It depends on who gets to decide what counts as a real invention.For patients, the message is clear: When a drug stays expensive long after its core patent expires, it’s not because it’s better. It’s because the system lets companies rewrite the rules.

Maggie Noe on 9 January 2026, AT 03:47 AM

This is wild. 🤯 So we're paying $500 for a pill that's chemically identical to a $5 one? And the system lets them do this? I mean... is this capitalism or just legalized robbery? 🤔