Congestion Stress Impact Estimator

Based on UK commuter study data (PSS-10 scale)

Recommended coping strategies:

Traffic congestion is a condition where vehicle demand outpaces road capacity, causing slower speeds and longer travel times. When you’re stuck in a sea of brake lights, it’s not just your schedule that suffers - your mind feels the strain too. This article unpacks how that daily gridlock chips away at mental health and overall well‑being, and it offers practical steps to protect yourself and your community.

Key Takeaways

- Longer commute times raise stress hormones and heighten anxiety.

- Noise and air pollution from idling traffic worsen mood and increase depression risk.

- Loss of perceived control during congestion amplifies cognitive overload.

- Urban‑planning interventions (e.g., dedicated bus lanes, flexible work hours) can lower mental‑health impacts.

- Personal coping tools - mindfulness, active travel, realistic scheduling - help mitigate daily strain.

What Exactly Is Congestion?

At its core, congestion means more cars on the road than the infrastructure can handle. During peak hours, the average speed can drop below 5 km/h, and queues stretch for kilometres. In the UK, the Department for Transport reports that commuters lose an average of 81 hours per year to traffic snarls. That’s 3 full days of idle time - and each minute stuck fuels a cascade of psychological stressors.

How Congestion Triggers Stress and Anxiety

Stress isn’t just a feeling; it’s a physiological response. When you’re caught in a jam, your body releases cortisol and adrenaline to prepare for action. Studies from the University of Leeds (2023) measured cortisol levels in 200 commuters and found a 27% increase after a 30‑minute traffic jam compared with a calm walk. The same researchers linked higher cortisol to elevated anxiety scores on the GAD‑7 questionnaire.

Key mechanisms include:

- Commute time the total duration spent traveling to and from work - longer trips reduce personal downtime, eroding recovery periods.

- Loss of control feeling powerless to change the situation - drivers perceive traffic as an uncontrollable external force, which amplifies stress.

- Cognitive load mental effort required to monitor traffic, make decisions, and stay safe - constant vigilance taxes the brain, leading to mental fatigue.

Beyond Stress: Links to Depression and Mood Disorders

Chronic exposure to congestion isn’t just a temporary irritant; it can seed deeper mood problems. A longitudinal study in Copenhagen (2022) tracked 1,500 adults for five years. Participants reporting “high‑traffic daily commutes” were 1.8 times more likely to develop clinical depression than those with short, smooth rides.

Two environmental factors intensify this risk:

- Air pollution the mixture of particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds from vehicle exhaust - exposure to PM2.5 has been associated with inflammation that may affect neurotransmitter function.

- Noise pollution continuous sound levels above 55 dB typical in busy corridors - research from Harvard (2021) links sustained traffic noise to reduced serotonin levels, a key mood regulator.

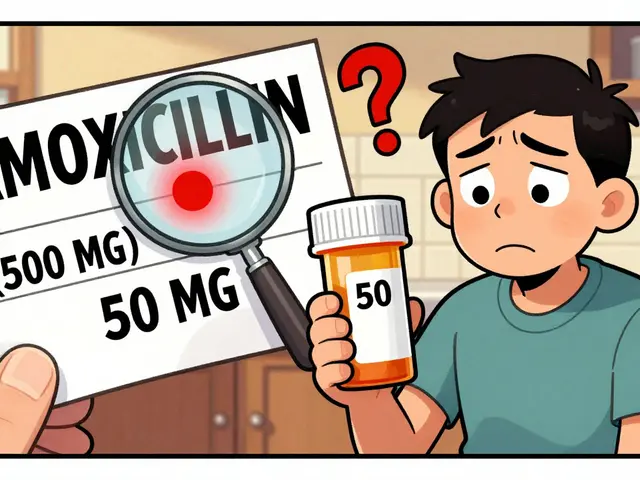

Quantifying the Mental‑Health Toll: A Comparison Table

| Congestion Level | Average Stress Score* (1‑10) | Depression Risk Increase | Sleep Quality Drop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤15 % capacity use) | 3 | 5 % | -2 % |

| Moderate (15‑30 % over capacity) | 5 | 12 % | -8 % |

| High (>30 % over capacity) | 8 | 22 % | -15 % |

*Stress score derived from the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS‑10) in surveys of UK commuters.

Urban Planning and Policy: Reducing the Burden

City‑wide solutions can lower the mental‑health impact of traffic bottlenecks. Key strategies include:

- Investing in Public transport buses, trams, and trains that move many passengers at once - dedicated bus lanes cut travel time by up to 30% in Bristol (2024).

- Implementing congestion‑charging zones - London’s scheme has cut inner‑city traffic by 15% and correspondingly lowered reported stress levels among commuters.

- Promoting active travel (cycling, walking) - a 2023 NHS report found cyclists report 40% lower anxiety scores than car drivers during peak hours.

- Encouraging flexible work hours or remote work - staggering start times reduces peak‑hour load by up to 20%.

When planners embed green spaces alongside roads, they also buffer noise and improve air quality, providing a double mental‑health boost.

Personal Coping Toolkit

Even if city‑wide reforms take time, you can protect your mind today:

- Plan ahead: Use real‑time traffic apps to choose the least‑congested route.

- Mindful breathing: A 5‑minute box‑breathing exercise (4‑4‑4‑4 seconds) lowers cortisol during a jam.

- Audio therapy: Soothing podcasts or binaural beats can mask intrusive engine noise.

- Active commuting: If feasible, bike or walk part of the journey to increase endorphins.

- Schedule buffers: Add a 10‑minute “mental‑health buffer” before important meetings to avoid arriving frazzled.

Checklist: Spotting Congestion‑Related Mental‑Health Warning Signs

- Persistent irritability or short‑tempered reactions at the end of the day.

- Frequent headaches or neck tension after driving.

- Difficulty falling asleep because you replay traffic scenarios.

- Increasing reliance on caffeine or smoking to stay alert during commutes.

- Feeling a loss of control or dread when thinking about the next drive.

If you notice two or more of these signs, consider adjusting your commute or seeking professional advice.

Future Outlook: What Might 2030 Hold?

Emerging technologies could reshape the congestion‑mental health landscape:

- Autonomous vehicles promise smoother flow, but early adopter studies warn of “automation anxiety.”

- Smart‑city traffic‑management AI can predict bottlenecks minutes ahead, offering proactive rerouting.

- Expanded high‑speed rail corridors may shift long‑distance commuters off highways entirely.

Policymakers who treat congestion as a public‑health issue, not just an infrastructure problem, will likely see the biggest gains in community well‑being.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does occasional traffic really affect mental health?

Yes. Even short, unexpected jams can trigger a spike in stress hormones. Repeated exposure can accumulate, raising the risk of anxiety over time.

Are cyclists immune to congestion‑related stress?

Not entirely, but studies show active commuters report lower perceived stress and higher mood scores compared with drivers, likely due to physical activity and greater sense of control.

How does air pollution from traffic influence depression?

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can cause systemic inflammation, which research links to altered neurotransmitter activity and higher rates of depressive symptoms.

Can flexible work hours really reduce my stress?

Yes. Shifting start times even by 30 minutes can move you out of the peak‑hour surge, cutting commute time and the associated cortisol response.

What quick mental‑health trick works while stuck in traffic?

Practice the 4‑4‑4‑4 box‑breathing technique: inhale for 4 seconds, hold for 4, exhale for 4, hold again for 4. Repeat five times to calm the nervous system.

Traffic congestion may feel unavoidable, but its mental‑health impact is not a fixed destiny. By understanding the science, advocating for smarter city design, and adopting personal coping tools, you can regain control over your mood and well‑being, even when the road ahead looks jammed.

Tammy Sinz on 22 October 2025, AT 17:05 PM

Traffic congestion isn’t just an inconvenience; it’s a neuroendocrine stressor that provokes cortisol dysregulation, amplifies sympathetic arousal, and overloads executive function circuits. The chronic exposure to sub‑optimal flow conditions creates a feedback loop where perceived loss of control fuels anxiety, which in turn deteriorates decision‑making capacity on the road. Evidence from the Leeds study you cited corroborates the hypothesis that even a 30‑minute jam can precipitate a measurable spike in the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal axis. When commuters repeatedly encounter these micro‑stress events, the allostatic load accumulates, leading to heightened vulnerability to mood disorders. Urban planners must therefore treat congestion as a public‑health externality rather than a mere transportation inefficiency.