When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the race to be the first generic version on the market isn’t just about speed-it’s about locking in market share for years. The first company to file a generic version and win regulatory approval doesn’t just get a head start. It often captures 70-80% of the entire generic market during its 180-day exclusivity window. And that lead? It doesn’t disappear after those six months. It sticks.

Why Being First Matters More Than You Think

The rules were set in 1984 by the Hatch-Waxman Act. It gave generic manufacturers a legal path to challenge patents and, if successful, granted them 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. That’s not just a reward-it’s a strategic lifeline. During those six months, no other generic can legally enter. That means the first filer gets to set the price, negotiate with pharmacies, and become the default choice for doctors and patients. But here’s the real kicker: even after those 180 days are up, the first mover still holds onto a massive share of the market. Data shows they often keep 30-40% of sales years later, while second entrants fight for 10-15%. Why? Because switching isn’t easy. Pharmacies don’t stock every version of a drug. They pick one-usually the first one they got. Why? Inventory costs. Training staff. System updates. Once a pharmacy has a generic in its system, they don’t want to swap it out unless forced. Doctors write prescriptions for the name they know. Patients refill the same pill they’ve been taking. All of that creates inertia. And inertia is a powerful barrier for anyone coming in second.The 180-Day Window Isn’t the Whole Story

Many assume the advantage ends when exclusivity expires. It doesn’t. The real value comes from what happens before and after. In those first six months, the first generic often sells at a price close to the brand-name drug-sometimes just 10-20% cheaper. That’s because there’s no competition yet. Later entrants are forced to slash prices to compete. But the first mover? They’ve already built relationships with distributors, secured shelf space, and trained pharmacy staff. They’ve become the default. McKinsey’s analysis found that first movers in specialty drugs-like injectables or treatments for rare conditions-can hold onto a 13-point market-share advantage over later entrants. In primary care drugs, the gap is smaller, but still meaningful. And if the first generic gets even one month ahead of the next competitor, that’s enough to lock in prescriber habits.Who Wins-and Who Gets Left Behind

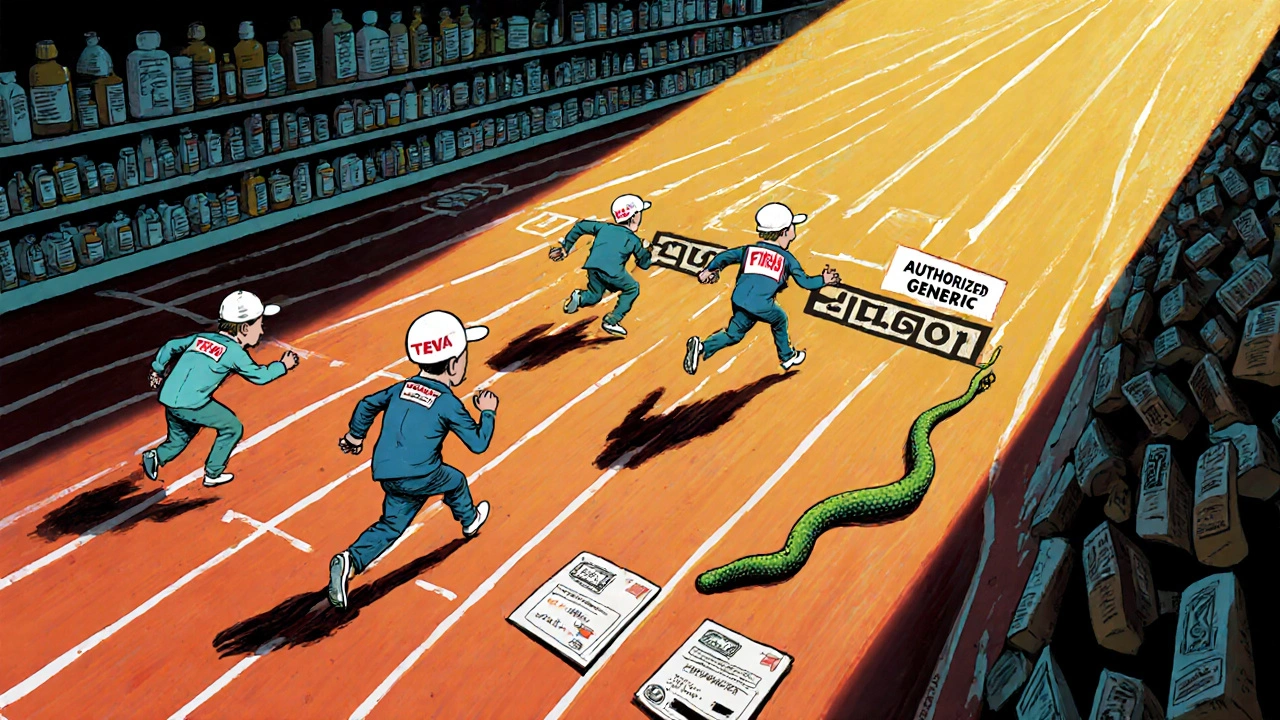

Not every first mover wins big. Size matters. Large pharmaceutical companies with existing generic divisions-like Teva, Mylan, or Sandoz-dominate the top spots. They have the resources to file patent challenges early, build manufacturing capacity ahead of time, and navigate complex FDA reviews. Their first-mover advantage? Often more than 10 percentage points above fair market share. Smaller companies? They struggle. Without deep pockets, they can’t afford to prepare for multiple scenarios. If the brand company launches an Authorized Generic (AG)-a version of the same drug sold by the original maker under a generic label-during the 180-day window, the first filer’s profits collapse. The FTC found AGs cut first-filer revenue by 4-8% at retail and 7-14% at wholesale. That’s a massive hit. Companies without experience in a specific therapeutic area? They capture only about half the advantage of seasoned players. Why? Because they don’t know how to talk to prescribers, how to respond to FDA requests, or how to scale production fast enough.

Complex Drugs Are the New Gold Rush

Simple pills? The race is crowded. But complex generics-like inhalers, eye drops, or injectables-are a different story. These drugs take years to develop. Fewer companies can make them. And that means fewer challengers. First movers in these categories see advantages of 15-20 percentage points above fair market share. Why? Because the FDA approval process is harder. Manufacturing is more technical. Supply chains are fragile. And once you’re in, it’s nearly impossible for someone else to catch up quickly. In 2023, over 60% of the first generic launches in complex drug categories came from just five companies. The barrier to entry isn’t just legal-it’s technical. That’s why the biggest players keep winning.How the Game Is Changing

The FTC has cracked down on “pay-for-delay” deals-where brand companies pay generic firms to delay entry. These deals used to keep generics off the market for years. Now, with stricter enforcement, first-mover launches are happening 6-9 months earlier on average. The FDA’s GDUFA III rules are also changing things. They aim to speed up approvals, which sounds good-but they’ve also made applications more complex. More paperwork. More data. More inspections. That favors big companies with regulatory teams. Smaller players find it harder to keep up. And then there’s the rise of biosimilars and specialty generics. These aren’t simple copies. They’re nuanced products that require deep expertise. The companies that invest in therapeutic knowledge now have a huge edge. One study found that first movers who expanded their drug’s approved uses within five years captured 13 percentage points more market share than those who didn’t.

The Real Secret: It’s Not About the Drug. It’s About the System.

The first-mover advantage isn’t about having the best formula. It’s about understanding how the system works. - Pharmacies stock one version to save money.- Doctors prescribe what they know.

- Patients stick with what they’ve been given.

- Distributors build relationships with the first supplier.

All of that creates a self-reinforcing loop. Even if a second generic is cheaper, it’s not easier. And in healthcare, ease often beats price. Dr. David Ridley from Duke University put it simply: “Patients with chronic diseases take these meds for years. They’re not going to switch unless there’s a powerful reason.” And in most cases, there isn’t one.

kim pu on 17 November 2025, AT 20:20 PM

lol so the whole system is just rigged for big pharma to keep their monopoly under the guise of 'generic competition'? 🤡 i mean, if you're the first to file, you get to charge brand prices for months? and the fda just lets them? this isn't capitalism, it's feudalism with pill bottles.