When your immune system is weakened-whether from disease, transplant, or the drugs meant to treat it-your body loses its natural defense system. That’s not just a medical fact; it’s a daily reality for millions. In the U.S. alone, about 24 million people live with autoimmune diseases that often require long-term immunosuppressant therapy. For them, every cough, scratch, or mosquito bite carries a heavier weight than it does for someone with a fully functioning immune system.

What most people don’t realize is that the very medications that keep these patients alive or comfortable can turn minor infections into life-threatening events. The risk isn’t theoretical. A 2012 meta-analysis of over 4,000 patients showed that those on corticosteroids had a 60% higher chance of developing serious infections than those not on them. That’s not a small increase. It’s a dramatic shift in risk.

How Immunosuppressants Work-and Why They’re Dangerous

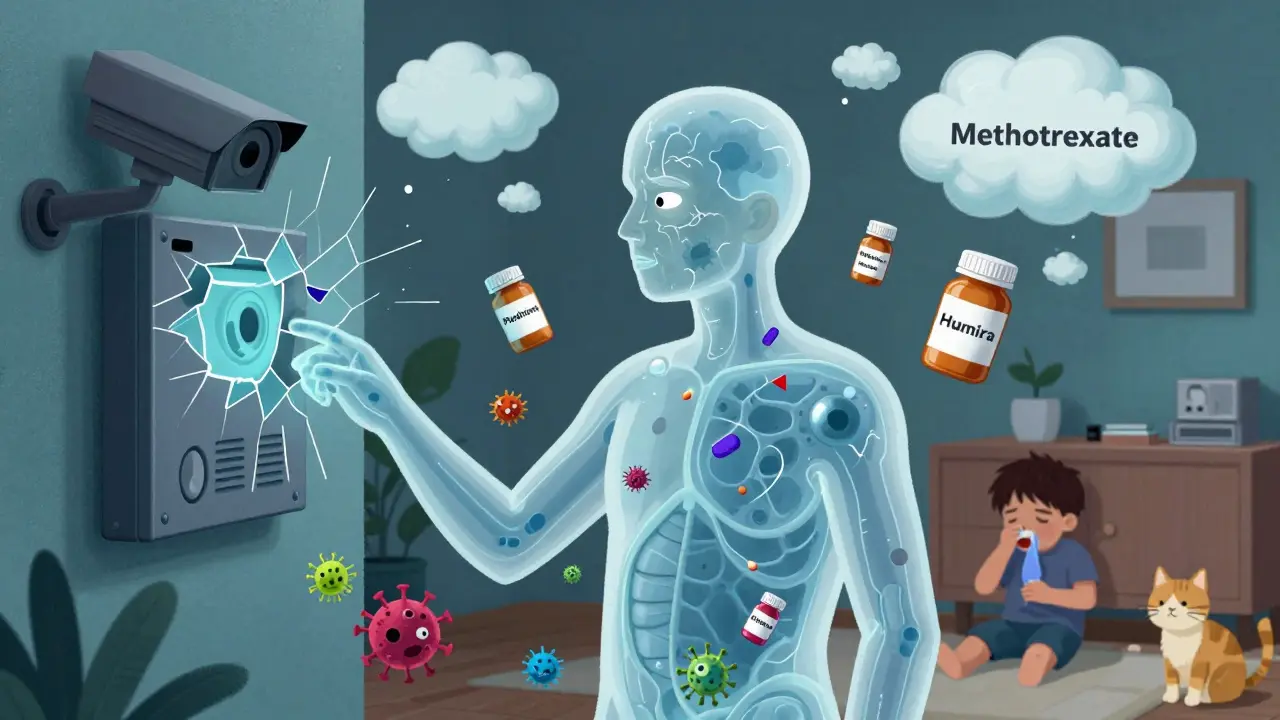

Immunosuppressants don’t just dial down inflammation. They shut down parts of your immune system. Think of your body as a security system. Normally, it patrols for threats: viruses, bacteria, fungi. Immunosuppressants disable the cameras, the motion sensors, and sometimes even the alarm system. That helps stop the immune system from attacking your own joints in rheumatoid arthritis or rejecting a transplanted kidney. But it also leaves you defenseless against things you’d normally shrug off.

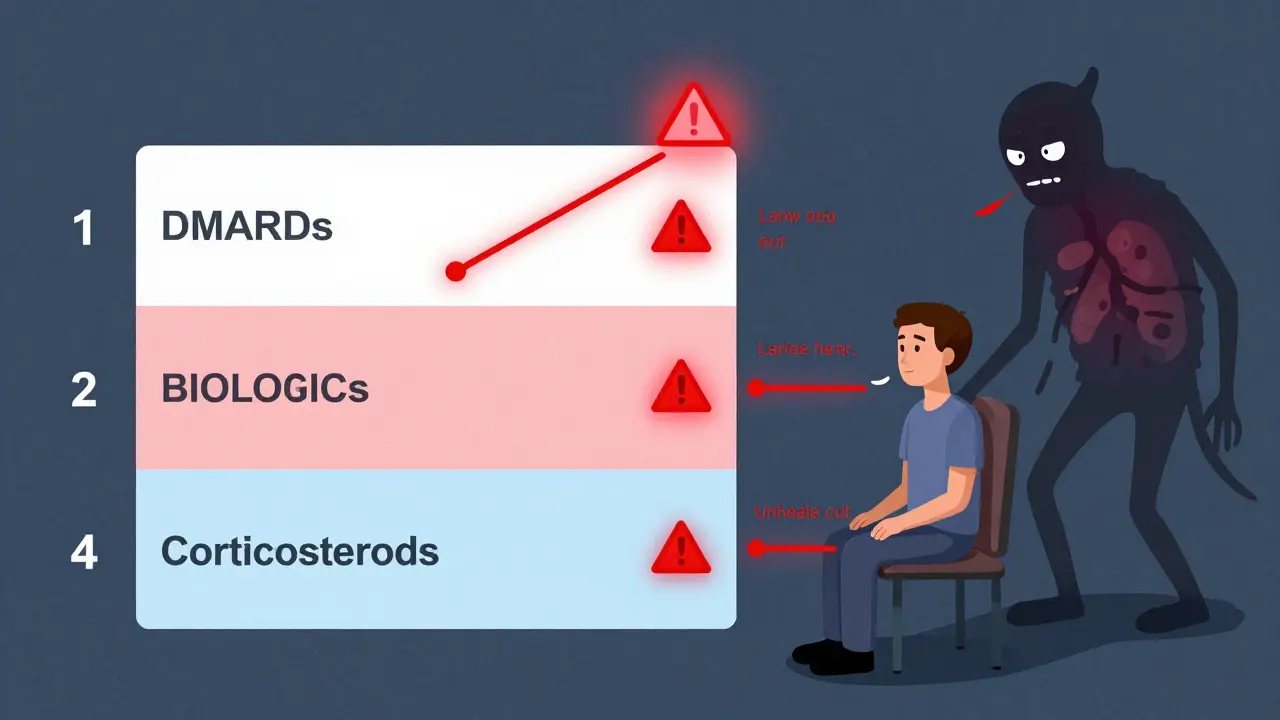

There are several classes of these drugs, each with different ways of weakening immunity:

- Corticosteroids like prednisone, dexamethasone, and methylprednisolone reduce immune cell production and suppress inflammation. But at doses above 20mg/day of prednisone equivalent-and especially if taken for more than two weeks-they significantly raise infection risk. A single course for a COPD flare might be low-risk. Long-term use for lupus or MS? That’s a different story.

- Conventional DMARDs like methotrexate and leflunomide work slower but still cut immune activity. Methotrexate, the most common, causes fatigue, nausea, and liver stress in many. About half of users stop taking it within a year because of side effects. Yet, for most, it’s still the best tool to control disease.

- Biologics target specific immune proteins, like TNF-alpha. Drugs like adalimumab (Humira) and infliximab (Remicade) are powerful. But they’re also linked to the highest infection rates among all classes. Herpes zoster (shingles), pneumonia, and even tuberculosis can flare up because these drugs block the immune signals that keep dormant infections in check.

- Calcineurin inhibitors like cyclosporine and tacrolimus are critical for transplant patients. They prevent rejection but increase the risk of viral infections like CMV, EBV, and even rare brain infections from the JC virus.

- Chemotherapy agents like cyclophosphamide are used in severe autoimmune cases. They’re not just immunosuppressive-they’re bone marrow poisons. That means low white blood cells, low platelets, and a sky-high risk of sepsis.

The worst part? Combining these drugs multiplies the danger. Taking steroids with methotrexate? That’s a known combo. Add a biologic on top? The infection risk doesn’t just go up-it explodes. Studies show the combination of steroids and other immunosuppressants leads to more opportunistic infections than either drug alone.

The Silent Infections: When Symptoms Don’t Show Up

One of the scariest things about being immunocompromised is that infections don’t always act like infections. You don’t get a high fever. You don’t feel achy. You might just feel tired. Or your cough might be so mild you think it’s allergies. That’s because corticosteroids blunt the body’s normal inflammatory response-the very signs that tell you something’s wrong.

Dr. Francisco Aberra and Dr. David Lichtenstein pointed out in 2005 that this masking effect makes diagnosis incredibly hard. A patient on high-dose steroids might have pneumonia but show no fever, no chills, no elevated white blood cell count. By the time it shows up on a chest X-ray, it’s often too late.

That’s why patients on immunosuppressants are taught to watch for subtle red flags:

- A cough that lingers longer than usual

- Unexplained fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest

- A low-grade temperature that never spikes but never drops

- Swelling or redness around a cut that doesn’t heal

- Diarrhea or abdominal pain without food poisoning

And then there are the infections you can’t even see. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), caused by the JC virus, is rare-but almost always fatal in immunocompromised patients. It attacks the brain. You don’t feel it coming. One day you’re fine. The next, you’re stumbling, confused, unable to speak. It’s not common. But it’s real. And it’s why doctors test for JC virus antibodies before starting certain drugs.

Vaccines: The Double-Edged Sword

People often assume vaccines are safe for everyone. Not true. Live vaccines-like the shingles vaccine (Zostavax), the nasal flu spray, or the MMR shot-are off-limits for most immunocompromised patients. Why? Because they contain weakened live viruses. In a healthy person, they trigger a harmless immune response. In someone on immunosuppressants? They can cause the disease they’re meant to prevent.

So what’s the solution? Get vaccinated before starting treatment. If you’re about to begin methotrexate or a biologic, your doctor should check your immunity to chickenpox, measles, hepatitis B, and tetanus. If you’re not immune, you get the shot-then wait at least two weeks before starting the drug.

Even then, it’s not perfect. Studies show vaccines often don’t work as well in immunocompromised patients. The flu shot might give you partial protection. The COVID-19 vaccine? You might need extra doses. The CDC now recommends a third primary dose for many immunocompromised people, followed by boosters every few months.

And don’t forget the non-vaccine protections. Handwashing for 20 seconds isn’t just advice-it’s a survival tactic. Alcohol-based sanitizer when soap isn’t available. Masks in crowded places. Avoiding people who are sick. Even petting a cat can be risky if you’re on heavy immunosuppression-cat scratch disease can turn deadly.

What the Data Really Says: The COVID-19 Surprise

Early in the pandemic, everyone assumed immunocompromised people would die at alarming rates from COVID-19. It made sense: no immune defense means no fight. But in 2021, Johns Hopkins researchers published a shocking finding: patients on immunosuppressants had outcomes similar to those without them.

Why? Experts still debate it. Maybe the drugs dampened the dangerous cytokine storms that kill some patients. Maybe the care was more aggressive. Maybe the immune system doesn’t need to be fully active to clear the virus. Whatever the reason, it changed the game. It taught doctors that blanket assumptions about immunosuppression and infection risk don’t always hold up.

But here’s the catch: that doesn’t mean it’s safe. It just means it’s more complex. Some patients still got very sick. Others didn’t. That’s why personalized care matters more than ever. Your risk isn’t just about the drug you’re on. It’s about your age, your other illnesses, your nutrition, your exposure to pathogens, and even your sleep quality.

Living With the Risk: Real Stories, Real Choices

Reddit threads from r/Rheumatoid and r/Transplant are full of raw, honest stories. One user wrote: "I got shingles on my face while on Humira. It felt like my nerves were on fire. I had to take two weeks off work. My doctor said it was "expected."" Another said: "Tacrolimus saved my kidney. I take 15 pills a day, get blood drawn every two weeks, and avoid crowds. It’s a trade-off. But I’m alive."

Patients don’t just take these drugs-they live with them. Every decision is a calculation. Is the joint pain worth the risk of pneumonia? Is the fatigue worth the chance to walk without pain? Is the monthly blood test worth the peace of mind?

For many, the answer is yes. Methotrexate might cause nausea, but it lets them play with their kids. A biologic might raise infection risk, but it lets them travel again. These aren’t just medications. They’re lifelines.

What You Can Do: Practical Steps for Safer Living

If you or someone you care about is immunocompromised, here’s what actually helps:

- Know your drug’s risks. Ask your doctor: "What infections is this drug most likely to cause?" Don’t just accept "it can cause infections." Get specific.

- Get blood work done regularly. CBC, liver, and kidney tests aren’t routine-they’re your early warning system. Methotrexate users need monthly checks. Don’t skip them.

- Get vaccinated early. If you’re on the fence about a vaccine, get it before starting immunosuppressants. Once you’re on them, options shrink.

- Wear a mask in hospitals, planes, and crowded stores. You’re not being paranoid. You’re being smart.

- Don’t ignore small symptoms. A lingering cough? A patch of skin that won’t heal? A fever that never hits 101 but stays at 99.5? Call your doctor. Don’t wait.

- Ask about alternatives. Is there a less risky drug that works? Sometimes switching from a biologic to a conventional DMARD reduces infection risk without losing effectiveness.

And remember: you’re not alone. About 7.6% of Americans live with autoimmune diseases. Millions are on these drugs. The medical community is learning fast. Newer drugs like JAK inhibitors aim to be more targeted, with fewer broad immune effects. Future tools-like genetic testing to predict who’s at highest risk for side effects-could make treatment safer.

But for now, the best defense is awareness, vigilance, and communication. Your immune system might be weakened. But your knowledge? That’s something you can build.

Can immunosuppressants cause long-term damage to the immune system?

Most immunosuppressants don’t permanently damage the immune system. Once you stop taking them, your immune function usually returns-though it can take weeks or months. Methotrexate and azathioprine may take 6-12 weeks to clear from your system. Biologics like TNF inhibitors can linger for months. But the immune system itself isn’t permanently broken. The risk is during treatment, not after.

Are natural remedies or supplements safe for immunocompromised patients?

Many supplements can interfere with immunosuppressants or worsen side effects. Echinacea, for example, can stimulate the immune system and trigger rejection or flare-ups. High-dose vitamin C, zinc, or turmeric might seem harmless, but they can alter how your body processes drugs like methotrexate or cyclosporine. Always talk to your doctor before taking anything-even "natural" products.

Do all immunocompromised patients have the same level of risk?

No. Risk varies wildly. A young person on low-dose prednisone for asthma has far lower risk than an older transplant patient on triple immunosuppression. Diabetes, obesity, smoking, and poor nutrition all raise infection risk. Your overall health matters as much as your medication.

Can you get sick from someone who’s been vaccinated?

Generally, no. Vaccinated people don’t spread live viruses unless they received a live vaccine themselves. The flu shot (injected) and most COVID-19 vaccines don’t contain live virus. The only exception is the nasal flu vaccine (FluMist), which contains a weakened live virus. Immunocompromised people should avoid close contact with anyone who just got that vaccine.

Is it safe to travel while on immunosuppressants?

Yes-but with caution. Avoid areas with poor sanitation, unclean water, or high rates of malaria or dengue. The CDC warns immunocompromised travelers are at higher risk for mosquito- and tick-borne diseases. Get travel-specific advice from your doctor. Carry a letter from your provider listing your medications. Bring extra prescriptions. And avoid large crowds during flu season or outbreaks.

Nina Catherine on 19 February 2026, AT 23:34 PM

Okay but real talk-my mom’s on methotrexate for RA and she’s been fine for 5 years, but she swears by hand sanitizer and refuses to hug anyone during flu season. I used to think she was overreacting… until last winter when her neighbor got pneumonia and ended up in the ICU. Now I get it. Small things matter. Also, she got her shingles shot BEFORE starting meds-doctors didn’t even mention it, but she called her rheumatologist and demanded it. Smart woman.